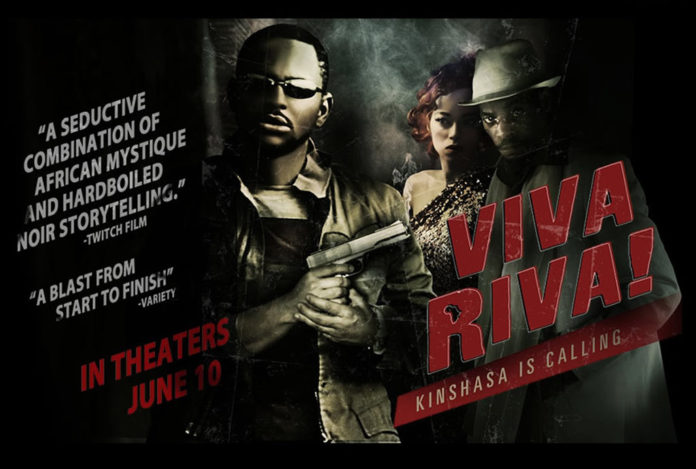

Viva Riva! makes good on its promise of sex, oil and scandal. The Congolese film noir written and directed by Djo Munga has been racking up awards at international film festivals with Time Out New York calling it “one of the best neo-noirs from anywhere in recent memory”. The film is showing at Cineplex Cinema, Garden City and for more insights into the mind of it’s first-time director, this interview by This is Africa tells more about Djo Munga.

TIA: What inspired you to make Viva Riva?

DM: I wanted to make a film that would allow me to talk about the reality of Kinshasa, and at the same time be entertaining, but I didn’t want to do it through social-realism, the typical documentary-like style of filming when trying to “capture” Africa, because that can be boring. I wanted to communicate to the masses. Culturally speaking, the Congolese — and black people in general — we have a need for cultural products that represent us in ways we can be proud of while remaining entertaining. This doesn’t mean I want to make films that ignore the problems; that’s not the case. I just wanted to experiment; I wanted to make a hugely entertaining film that could also reflect the last 20 years of Kinshasa’s history.

TIA: I notice that African filmmakers can feel pressured to make films that are politically charged or socially engaged. Did you feel that pressure?

DM: Well, I don’t see it as a pressure. I think it’s necessary at this stage in our history, as Congolese and Africans, to have a political point of view. There are some important issues that we should talk about, and it’s perfectly normal to talk about them, but I think the way we talk about these issues is also very important. In other words, the form the message takes to reach the audience is important. The way I see it, knowing the level of literacy in the Congo, you can’t as a filmmaker go, “I’m going to make a film about this complex situation and if people don’t get it that’s their problem.” I was inspired by what Latin American writers did many years ago. I remember a guy by the name of Eduardo Galeano; he wrote the book… I forgot the title in English but you can check it, Les Veines Ouvertes de l’Amerique Latine (Open Veins of Latin America) and actually he was explaining the history of Latin America, but he did it as a soap opera to make it easy for people to understand and to be entertained. When I read that book as a student, I was like wow!, maybe this is the way we should do it. We need to find ways to reach the masses when talking about important issues, and you can do this while being entertaining.

TIA: I hear that most of the actors in Viva Riva! weren’t professionally trained. What was the rehearsal and casting process like?

DM: In Kinshasa, like in many poor countries, you have a lot of artists – I mean people who are doing what they do for the love of it; it’s the meaning of their lives, and they don’t do it for the money or for whatever reason. So in the misery of Congo we have a kind of luxury to have all these artists available and ready to work. So I said to these guys, “You have a lot of talent and you are good at what you do, but let’s go into a workshop where you will learn the techniques of working with the camera, and of working in film. And they came and worked for two months, you know, just discovering their bodies and how to work with the camera, etc. And after that, we stopped for a year — I mean I sent them back to their daily lives and they came back the next year for production. Then they started to work with an acting coach in terms of developing their characters and [learning] how to get deep into a script. After two months of this, we started rehearsing. I gave them the script, and they rehearsed every day, maybe like three hours every morning. So yeah, it was a real pleasure. It didn’t feel like work, to tell you the truth. We had a lot of fun…I think (laughs).

TIA: I think most creative works reflect the artist in some way. If I am right, how do you personally relate to the characters of the film?

DM: (Laughs). That’s a tricky question. Well, I relate to many of them, so it’s difficult to say which one is closest to me because all of them are a part of me in a way. So I can see how “the commander” was more or less like a tyrant, but suddenly she was stuck in a situation and she started to change and then she becomes someone else — that happens to all of us. And with Riva, I can see also the way he avoids facing problems, and how his family’s problems are like mine. So all of them are like me in some ways. I think the way I write stories, I mean because I have many characters, is a way of putting yourself in various situations and trying to be as true as possible to the character and different situations.

TIA: The film has been traveling the festival circuit for a while now. Where are some of the places it’s screened?

DM: All over the world, more or less. We showed it in Kinshasa first as a test, then we screened it at the Toronto Film Festival, Berlin Film Festival, at festivals in Austin, Texas, France, England, Ireland and Hong Kong. It was very surprising that the film sold out in Hong Kong. This says something, actually, because we often think that China’s too far from us, and I thought they might say this is not for us. But why should they say that? People are interested in stories, no matter where they’re from. So for me, it was very good screening in Hong Kong. I was really amazed by the audience – they were really warm, they liked the film, and I had a really exciting interaction with them afterwards, so I was really happy; I was really pleased with the audience.

TIA: So are you surprised with all the positive reviews that your film has earned?

DM: Totally, totally surprised. Look at it from this point of view: I studied in Europe, in film school, so from the European point of view, you have this sense that, well, America is only interested in American films which is basically Hollywood and maybe some independent films, and that the rest of the world really doesn’t exist and Africa exists even less. That’s the point of view we had. But then the film was shown at the Toronto Film Festival and an American distributor was the first to buy the film and actually, the film’s first theatrical release [in the States] will be in New York, which is a sign really, a really big sign that maybe I was wrong to think the way I did. I mean since September, when the film opened in Toronto, it went really deep into my mind – I was thinking what does that mean to me now? It also broadened my vision of America: So “Okay, we like your film,” so I’m welcome. They took this film as they would a French film with Catherine Deneuve; I mean, she’s a bigger actress but still, it says something. Also, as a black person, it says something that I don’t have the feeling of [being] a sellout or someone who made a film just for Westerners. I feel like I’m just a filmmaker who made a film that people enjoyed. So it was definitely a big surprise, and that surprise was confirmed at the SXSW Film Festival and also yesterday, when I came to Baltimore, by the reception I got. So yeah, all the positive reviews have been a big surprise, a really big surprise.

TIA: It seems like our cultural backgrounds often influence the ways in which we interact with films. How has the reception been different in different parts of the world?

DM: African audiences loved it, at least in Congo; it was a big thing. But I was surprised that people [at film festivals] in America found the film violent. There were a lot of comments about that. I was surprised because they have all these action movies and TV shows on American TV. So there must be a reason why they find the film violent. I think maybe it’s because of the way the film is shot – it’s a bit different from the films they’re used to seeing. It’s not shot like a documentary but I think it takes you close to the characters the way a documentary takes you close to real people, so they get into the story more and feel the violence a bit more. In Hong Kong, they said the same thing. They said we are used to Chinese action movies, but we know they’re not real. But in Europe they didn’t say that. They felt it was different, so those are the type of reactions I received. Africans didn’t comment on the violence at all. Maybe because part of it was reality, I don’t know, but the African critics and journalists have been very, very supportive of the film – especially Nigerians. They feel that maybe this film is a change or offers a possibility for change for the industry in the future. I hope it will. And I’m really happy about it.

TIA: One of the recurrent criticisms of the film is that it portrays African women in negative, stereotypical ways. How do you respond to that?

DM: Well, some have said “he portrays women in a negative perspective,” but others have said I’m a feminist. Of course, I prefer to think of myself as a feminist.

Women face big problems in our society, especially in Congo, and I think I’ve tried to address these problems through the film’s female characters. Nora, for instance, is a beautiful woman trapped in her world and in a particular life, but with Riva, maybe she has the possibility to escape. Then there’s the commander who is maneuvering in society and tries to be free, but she can’t really, and her friend, Malou, and also the women of GM. It’s like different perspectives on Congolese women I tried to put. I don’t think I was negative in that sense. I tried to look at reality and of course, I could talk about the happy women who just got married and life is fantastic and all that, but in a country that is 167th poorest in the world, life is not easy and especially not for women, so that’s what I tried to show.

TIA: Since this is your first feature film, perhaps it’s too early to talk about legacy. Nonetheless, how would you like to be remembered as a filmmaker? And will all your subsequent films take place in African settings?

DM: Well, if people remember the films I made and the stories I told and enjoyed them, I would be happy. When I think about Sergio Leone, I don’t think about him being Italian – I just think about the great movies he made. Or if I think about Fritz Lang, I don’t think of him as being German or going to the West and then coming back – I just think how great of an artist he was. So I think of myself as an artist, and as an artist I try to do films in different places – which I have done. I shot a documentary in Ireland a long time ago, I’ve had projects in various parts of the world, and it’s important to me that I stick to that.

TIA: So what’s the film industry like in DR Congo?

DM: Nothing. There’s no industry in the classical sense, because when you talk about an industry, it means that there’s a structure, it means there are schools, there are systems in place for raising funds, hiring people, making films, and also finishing the films as in doing post-production work with all these labs and infrastructure to release the films once they’re made in order to recoup your costs. That does not exist; we only have what I call “gunmen”, like me, and various directors. We try to find opportunities to make films, which is basically as tough as robbing a bank, but that’s what we do. But I hope there will be an industry 20 years from now. One part of my work is that I do training programs. I try to help young filmmakers learn their craft, so that one day they can make films themselves.

TIA: What is your advice to aspiring young African filmmakers?

DM: Study. It’s very, very important. I hope I don’t sound too conservative, but still it’s important to be able to read great writers – like James Baldwin, a fantastic writer, Chester Himes, a fantastic writer – they are all very big writers, including African writers like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. Those are some of the more famous ones. And also to watch a lot of movies, classical movies. I mean I strongly believe education is the key to development. It’s almost impossible to develop without an education, except for a few people.

TIA: What are some of your future plans?

DM: First I’ll try to survive, which means I’ll try to find a way to make the next film. And making a film is also interacting with the industry. It means having a story and finding partners to invest. You know, I’m just in the business like everybody else, and I’m a small fish. So I’ll see where there’s a possibility for the next film, and I’ll try to do something.

TIA: Who are some actors and directors that you would love to collaborate with?

DM: I think Number One on that list would be Forest Whitaker. If I have the opportunity to work with him, I definitely will. I would also love to maybe adapt a book by someone like Chinua Achebe, or Alain Mabanckou, who is a Congolese writer. I think it would be challenging, and it would be something very interesting to do. I mean if I had the money, I would definitely do it, because I would love to bring his (Mabanckou’s) work to a bigger audience.

TIA: Lastly, what is a common misconception about living in Kinshasa that you would like to dispel?

DM: Misconceptions… I think the biggest one is… I want people to know that Kinshasa is actually a safe place, that most of the Congo is very safe. People refer to the Congo as this heart of darkness and this place where you can’t really live properly, which is not true – not at all true. I think this is the biggest misconception about the Congo.

Interview by Yves-Alec Tambashe